Sesquicentennial

As 2017 is the sesquicentennial year for John Muir’s thousand-mile walk across the southeastern U.S. (1867-68), it is likely that many people will be attempting to trace his path. After largely retiring from a forty-year career as a land and environmental conservation professional in the same region of our country, I've been inspired to retrace the path of Muir’s long walk myself, but with a different focus—that being by telling the story of land conservation along the route of Muir's Southern Trek. An account of conserved lands and protected natural areas along Muir's Southern walking route fits nicely with the mission of the organization for which I now serve as president -- Southern Conservation Partners -- which is dedicated to enhancing protection, restoration, and greater public awareness of the natural heritage of the southern U.S.

At my age, I was not particularly interested in walking 1,000 miles on road shoulders. I had no interest in recreating Muir’s rapid pace (practically a self-imposed forced march) and starvation rations—let alone contracting malaria along the way as Muir did! I would not literally hike the whole route of the then 29-year-old John Muir, but I decided to take a different perspective on his adventure. I would follow Muir’s route largely by personal vehicle, with periodic short walks along the way. I segmented my examination of his route into sections spread over more than a year.

My intent was to observe and describe the publicly accessible parks, nature preserves, forests and wildlife management areas, and other recreational areas along Muir’s walking route, in homage and testimony to the success story of land conservation in the southeastern U.S. I hope my account may educate and inspire others to enjoy 21st-century natural assets, many of them protected, along the route John Muir took 150 years ago. I intend this to be a short story on the progress of land conservation in the southern U.S.

I welcome your suggestions for improvements to this account! Please offer your suggested additions or corrections directly to me.

|

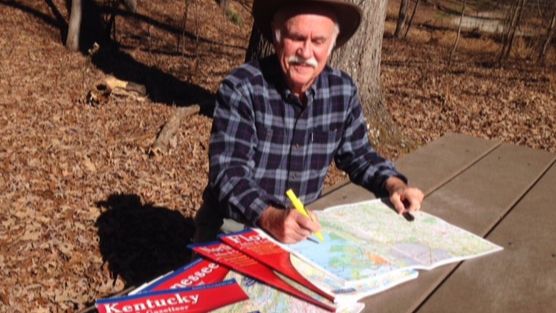

Author of this Story: Chuck Roe

Roe’s professional career includes being the founding manager of the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program, founding director of the Conservation Trust for North Carolina, and Southeast U.S. Region program director for

the Land Trust Alliance. Contact him HERE. |

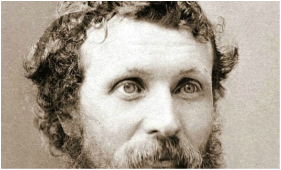

John Muir

My principal guide for this project

is John Muir’s own memoirs of his journey, composed years after his trek from his notes, which were edited and published posthumously in 1916 as A Thousand-Mile Walk To the Gulf. |

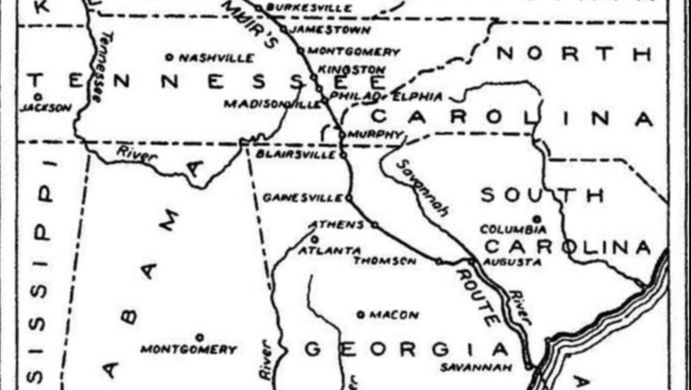

Get Started on the Route

View the map published with Muir's A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf, and begin reading Chuck Roe's exploration of the route . . . or use the menu at top of this page to read by state.

|

O V E R V I E WJohn Muir's Inspiration

|