Florida Part II: journey's end on the Gulf Coast

Walking west from Gainesville, Muir found the landscape drier with more exposed limestone, coral, and shells, and he passed cotton plantations with more comfortable residences (as represented by the Haile Homestead) than the squalid hovels he’d encountered on his walk across the northeastern Florida peninsula. Again Muir was impressed by beautiful groves of magnolia on edges of ponds and stream banks “festooned” with graceful vines and Tillandsia (Spanish moss). “[I]ts showy crimson fruit, and its magnificent fragrant white flowers make Magnolia grandiflora the most lovable of Florida trees.” But elsewhere Muir admired “sunny areas” forested by longleaf and “Cuban pines,” accompanied by “fine grasses and solidagoes.”

A modern traveler on Muir’s route will continue west from Gainesville on FL Route 24 (Archer Road), soon passing under another north-south modern highway (Interstate 75). Again you are passing through a heavily drained and altered landscape that has been largely converted for industrial forestry, agriculture, and pine plantations.

Muir, after passing a few squalid, impoverished residences, found the home of a prosperous farmer and former Confederate army officer, who courteously provided him refuge and hospitality. After offering food and conversation, Captain Simmons directed him to explore a fine palmetto grove on a rich hummock of nearly 7 miles length and 3 mile breadth--although getting there required him to make a brutal transect through a jungle of vines and briars. It is possible that the ridge forming the palmetto hummock that Muir visited may now be called Devil’s Hammock, located southwest of the city of Bronson. One of Florida’s magical springs, the Blue Spring, emerges at the northern end of this ancient sand ridge. But this hammock is in private ownership and access would be difficult. You’ll have to go farther off Muir’s route to enjoy public access to some of the many springs and crystal-clear streams to be found in other Florida state parks and preserves in the larger region. If you have some extra time to drive another hour south of Muir’s route, you might be interested in seeing more of the natural landscapes, ecosystems, and wildlife that Muir would have traipsed through by exploring parts of the 53,587-acre Goethe State Forest.

A day more of walking from the home and hospitality of Capt. Simmons, Muir on October 22 reached the sea on the Gulf of Mexico side of Florida at the Cedar Keys. Miles before reaching the coast, Muir sensed its presence by “the scent of the salt sea breeze.” And then “emerging from a multitude of tropical plants, I beheld the Gulf of Mexico stretching away unbounded, except by the sky … as I stood on the strand, gazing out on the burnished, treeless plain” of water.

An excellent choice for a modern traveler to witness natural habitats and ecosystems similar to those Muir would have seen is to visit Waccasassa Bay Preserve State Park (additional hiking information). Here 34,000 acres of public lands encompass pine and palmetto dominated ridges or hummocks, cypress forests, extensive tidal creeks and salt marshes, and on to the bay and coast for fishing and boating access. Wildlife like deer, otter, and turkey are common. Large numbers of migratory and resident birds populate the Waccasassa Bay area, along with notable and frequent sightings of bald eagles and marine manatees.

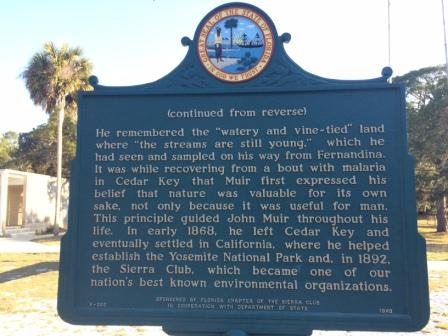

When Muir reached the empty harbor of Cedar Key, he discovered that the next expected ship coming from Galveston, Texas, to load timber from the nearby sawmills would not arrive for several more weeks. So he hired on with a sawmill owner and went to work for his food and lodging, once again offered in the home of his benefactor. But within a few days Muir’s intention to ship across the Gulf to the “famous flower-beds of Texas” was confounded when he was struck down by severe malaria. His hosts nursed him back from brink of death for the next three months. He recovered slowly – occasionally emerging from his bed to sit and contemplate beneath Spanish moss–draped live-oak trees, watch birds feeding on the shore, or admire a variety of wading birds and flocks of many other delightful birds in the forests and along the margins of the mangroves of the island keys. After he regained a modicum of strength, Muir was able, in January 1868, to board a small ship that sailed out among the coral reefs beyond the Cedar Keys harbor and on to Havana, Cuba. He took a brief sojourn in that port city, before reconsidering his directions and life goals and heading on to California.

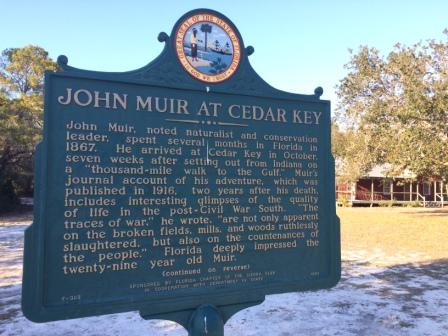

You too will reach Cedar Keys by FL Route 24, shortly after your stop in the Waccasassa Bay Preserve State Park, again crossing the Gulf Coast branch of the Florida Wildlife Corridor. Linger awhile in Cedar Keys (hopefully not for three months recovering from malaria like Muir!). Enjoy the cluster of dozens of mangrove-lined sea islands known as “keys.” A good way to delve into Gulf Coast ecosystems is to visit the 5,000-acre Cedar Key Scrub State Reserve, with its rare Florida scrub natural community, coastal forests, and tidal marshes. Spend some time visiting Cedar Key Museum State Park. The museum gives visitors an opportunity to imagine themselves as John Muir by walking past oaks and pines down to view the wildlife of Cedar Key’s salt marshes and beach. A commemorative marker on the museum’s 14 acres honors John Muir.

This section of Florida on the Gulf Coast near Cedar Keys remains one of the least-populated parts of the state (lots of wildlife, but relatively few people), and is the focus of efforts to increase the amount of protected ecosystems and natural areas on Florida’s Gulf coastline. The Lower Suwanee National Wildlife Refuge is located slightly north of Cedar Keys at the lower end of the Suwanee River (downstream from Fanning Springs and Manatee Springs State Parks) and on the Gulf Coast.

Even if you do not sail for Cuba from Cedar Key, you may arrange to rent a boat to enjoy seeing the Gulf Coast from a marine perspective, and for offshore fishing or wildlife watching. If you wish to visit Havana, you’ll probably need to fly or take a cruise ship from Tampa.

Florida has benefited from a very successful combination of public and private efforts to protect and conserve its amazingly diverse biological resources and environmental heritage. In previous decades national, state, and local government agencies took the lead in preserving the state’s land, water and wildlife resources. Now private land and wildlife conservancies shoulder primary leadership for Florida’s environmental protection. The most active private land trusts in the vicinity of Muir’s route are the Alachua Conservation Trust, the Conservation Trust for Florida , and the North Florida Land Trust. In addition, Florida Audubon , the Florida Trail Association , and the Florida Wildlife Federation have impressive statewide agendas and success records in environmental protection and education. While state governmental funding for land and water conservation in Florida was one of the largest in the country--amounting to over $300 million each year, until the successful Florida Forever Program was savagely diminished some eight years ago--state field offices of several national and international environmental organizations, including The Nature Conservancy, The Conservation Fund , and Trust for Public Land, were very active as well in preserving ecological resources and establishing public parks and wildlife management areas in the state.

A modern traveler on Muir’s route will continue west from Gainesville on FL Route 24 (Archer Road), soon passing under another north-south modern highway (Interstate 75). Again you are passing through a heavily drained and altered landscape that has been largely converted for industrial forestry, agriculture, and pine plantations.

Muir, after passing a few squalid, impoverished residences, found the home of a prosperous farmer and former Confederate army officer, who courteously provided him refuge and hospitality. After offering food and conversation, Captain Simmons directed him to explore a fine palmetto grove on a rich hummock of nearly 7 miles length and 3 mile breadth--although getting there required him to make a brutal transect through a jungle of vines and briars. It is possible that the ridge forming the palmetto hummock that Muir visited may now be called Devil’s Hammock, located southwest of the city of Bronson. One of Florida’s magical springs, the Blue Spring, emerges at the northern end of this ancient sand ridge. But this hammock is in private ownership and access would be difficult. You’ll have to go farther off Muir’s route to enjoy public access to some of the many springs and crystal-clear streams to be found in other Florida state parks and preserves in the larger region. If you have some extra time to drive another hour south of Muir’s route, you might be interested in seeing more of the natural landscapes, ecosystems, and wildlife that Muir would have traipsed through by exploring parts of the 53,587-acre Goethe State Forest.

A day more of walking from the home and hospitality of Capt. Simmons, Muir on October 22 reached the sea on the Gulf of Mexico side of Florida at the Cedar Keys. Miles before reaching the coast, Muir sensed its presence by “the scent of the salt sea breeze.” And then “emerging from a multitude of tropical plants, I beheld the Gulf of Mexico stretching away unbounded, except by the sky … as I stood on the strand, gazing out on the burnished, treeless plain” of water.

An excellent choice for a modern traveler to witness natural habitats and ecosystems similar to those Muir would have seen is to visit Waccasassa Bay Preserve State Park (additional hiking information). Here 34,000 acres of public lands encompass pine and palmetto dominated ridges or hummocks, cypress forests, extensive tidal creeks and salt marshes, and on to the bay and coast for fishing and boating access. Wildlife like deer, otter, and turkey are common. Large numbers of migratory and resident birds populate the Waccasassa Bay area, along with notable and frequent sightings of bald eagles and marine manatees.

When Muir reached the empty harbor of Cedar Key, he discovered that the next expected ship coming from Galveston, Texas, to load timber from the nearby sawmills would not arrive for several more weeks. So he hired on with a sawmill owner and went to work for his food and lodging, once again offered in the home of his benefactor. But within a few days Muir’s intention to ship across the Gulf to the “famous flower-beds of Texas” was confounded when he was struck down by severe malaria. His hosts nursed him back from brink of death for the next three months. He recovered slowly – occasionally emerging from his bed to sit and contemplate beneath Spanish moss–draped live-oak trees, watch birds feeding on the shore, or admire a variety of wading birds and flocks of many other delightful birds in the forests and along the margins of the mangroves of the island keys. After he regained a modicum of strength, Muir was able, in January 1868, to board a small ship that sailed out among the coral reefs beyond the Cedar Keys harbor and on to Havana, Cuba. He took a brief sojourn in that port city, before reconsidering his directions and life goals and heading on to California.

You too will reach Cedar Keys by FL Route 24, shortly after your stop in the Waccasassa Bay Preserve State Park, again crossing the Gulf Coast branch of the Florida Wildlife Corridor. Linger awhile in Cedar Keys (hopefully not for three months recovering from malaria like Muir!). Enjoy the cluster of dozens of mangrove-lined sea islands known as “keys.” A good way to delve into Gulf Coast ecosystems is to visit the 5,000-acre Cedar Key Scrub State Reserve, with its rare Florida scrub natural community, coastal forests, and tidal marshes. Spend some time visiting Cedar Key Museum State Park. The museum gives visitors an opportunity to imagine themselves as John Muir by walking past oaks and pines down to view the wildlife of Cedar Key’s salt marshes and beach. A commemorative marker on the museum’s 14 acres honors John Muir.

This section of Florida on the Gulf Coast near Cedar Keys remains one of the least-populated parts of the state (lots of wildlife, but relatively few people), and is the focus of efforts to increase the amount of protected ecosystems and natural areas on Florida’s Gulf coastline. The Lower Suwanee National Wildlife Refuge is located slightly north of Cedar Keys at the lower end of the Suwanee River (downstream from Fanning Springs and Manatee Springs State Parks) and on the Gulf Coast.

Even if you do not sail for Cuba from Cedar Key, you may arrange to rent a boat to enjoy seeing the Gulf Coast from a marine perspective, and for offshore fishing or wildlife watching. If you wish to visit Havana, you’ll probably need to fly or take a cruise ship from Tampa.

Florida has benefited from a very successful combination of public and private efforts to protect and conserve its amazingly diverse biological resources and environmental heritage. In previous decades national, state, and local government agencies took the lead in preserving the state’s land, water and wildlife resources. Now private land and wildlife conservancies shoulder primary leadership for Florida’s environmental protection. The most active private land trusts in the vicinity of Muir’s route are the Alachua Conservation Trust, the Conservation Trust for Florida , and the North Florida Land Trust. In addition, Florida Audubon , the Florida Trail Association , and the Florida Wildlife Federation have impressive statewide agendas and success records in environmental protection and education. While state governmental funding for land and water conservation in Florida was one of the largest in the country--amounting to over $300 million each year, until the successful Florida Forever Program was savagely diminished some eight years ago--state field offices of several national and international environmental organizations, including The Nature Conservancy, The Conservation Fund , and Trust for Public Land, were very active as well in preserving ecological resources and establishing public parks and wildlife management areas in the state.

Now I encourage you to follow the route of John Muir’s 1,000-mile trek across part of the southeastern U.S. You may choose to hike or bike the whole way, or like me poke about by car and enjoy multiple walks or even kayaking paddles to immerse in the wonderful natural diversity and beauty, and human culture and history that you will find along the way. Learn from and linger at the many museums, nature centers, parks and wildlife refuges, rivers and nature preserves, and even a few cemeteries. Celebrate the many successes in land and wildlife conservation. Learn more about the “southern U.S. conservation story,” and take your time. Allow time for diversions and detours, and seek out much more delectable food and drink than Muir managed (the South is famous, after all, for its diverse foods, nature, and culture). LEARN and ENJOY! --Chuck Roe